What does it mean to lose a language? Deep knowledge, passed down over millennia—gone. Ways of thinking about the land, the sea, the sky, and the flora and fauna that inhabit them. Rituals and recipes. Myths and memories, erased. And for those who spoke the language, it means losing a part of themselves.

It happens every three months. A language—an irreplaceable key to understanding the world—fades away. By the end of the century, as much as 90% of the world’s 6,500 languages will be gone forever.

Languages are prisms through which we look at the world. A shared understanding that binds a people together. A diversity of languages encourages a diversity of thought, of perspectives, of sense-making. Every language tells us a little bit about who we are. When a language dies, a sliver of our shared culture vanishes, and humanity is poorer for the loss.

90%

By the end of the century, as much as 90% of the world’s 6,500 languages will be gone forever.

The language of the Fulani people of West Africa, known as Pulaar, is spoken by over 40 million people, so it’s not in immediate danger. However, for most of its history, Pulaar never had an alphabet. Fulani are increasingly doing business, finding information, and expressing themselves via text on mobile devices. And if they can’t communicate digitally with an alphabet that reflects the language they speak, they will use other writing systems, and one day, other languages.

For languages that have no digital script, the writing is on the wall.

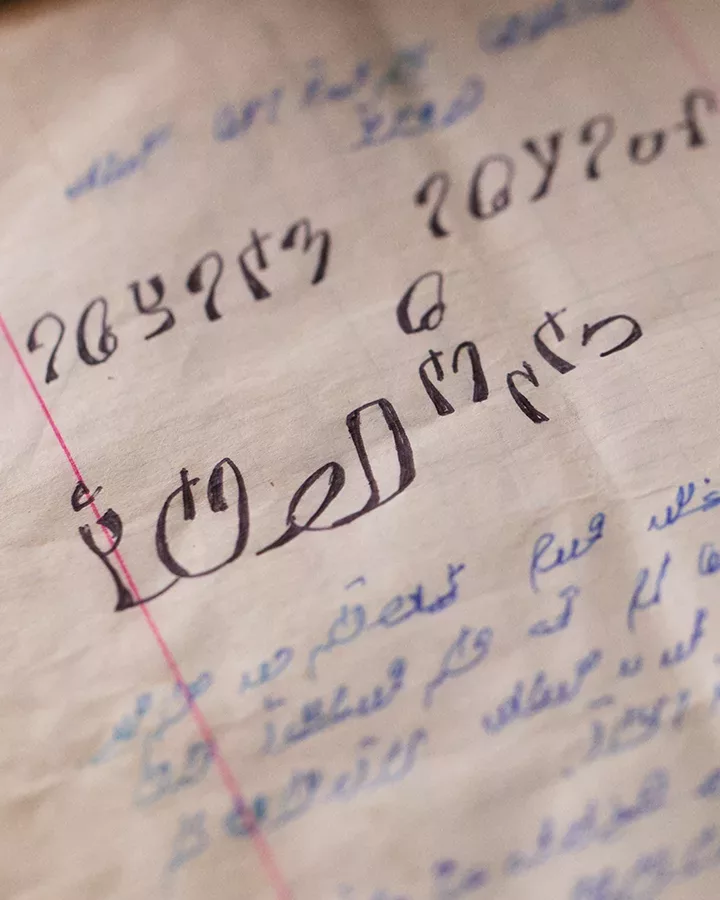

Thirty years ago, two Fulani brothers took it upon themselves to reverse this inevitability. They created an alphabet that would one day spread across the global Fulani community and beyond. It would come to be known as ADLaM, an acronym using the alphabet’s first four letters, which stands for Alkule Dandayɗe Leñol Mulugol, or “the alphabet that protects the people from vanishing.”

Image carousel

Vanished language, vanished people

Over the centuries, languages are born, live and die. Peoples and their languages migrate and mingle with other groups. Conquerors co-opt languages and alphabets or impose them onto their subjects. The properties of a language and its alphabet—the number of characters, their shapes, their representations of sounds—are the results of a long and messy social process, which often leads to people using an alphabet that’s not their own, not fitted to their spoken language.

“In parts of Africa, anyone who doesn’t know how to read or write in French is considered illiterate,” says Abdoulaye Barry. It is not uncommon for regimes, especially those with a colonial heritage, to be suspicious of efforts to popularize “unofficial” writing systems. Policing the written word is a way to exert control.

Government communication is provided in a language that more than three quarters of the population does not understand. There is a purpose to that. Maybe you don’t want people to understand the laws because you want to rule them in a certain way.

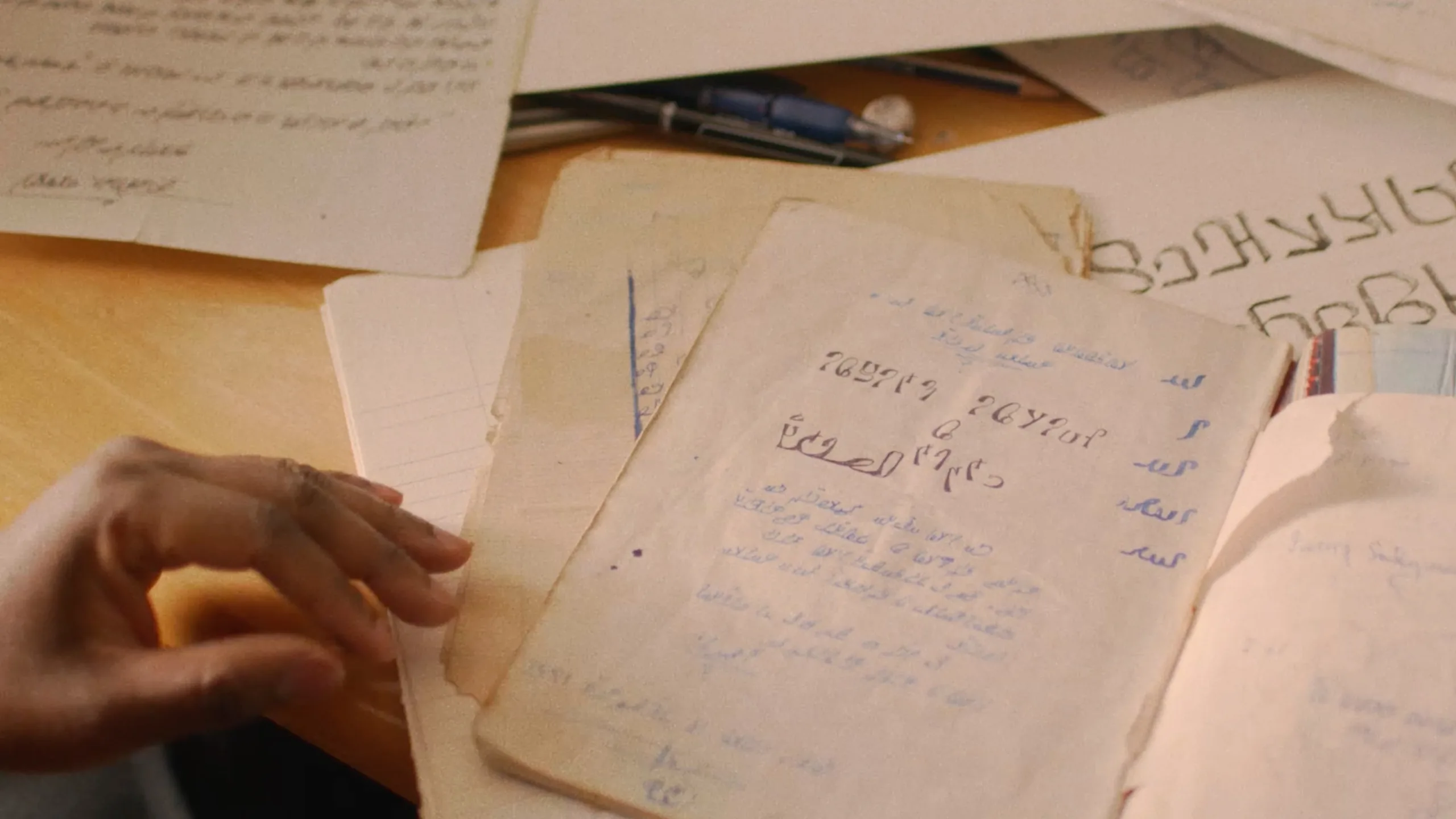

More than 30 years ago, Abdoulaye sat, pen in hand, in a back room at his home in Nzérékoré, Guinea. He wasn’t alone – an older woman, his friend’s mother, sat with him, waiting for him to prepare his pen and paper.

When she began to speak, Abdoulaye’s hand moved rapidly across the page. The woman kept her voice low, as though she didn’t want anyone else in the house to hear what she had to say. Abdoulaye kept pace with the woman’s dictation, until she came to an abrupt stop.

The woman hesitated, and for a moment, time stood still. She looked down at her hands.

“Are you finished?” asked Abdoulaye.

On this occasion, the woman had specifically asked if Abdoulaye could help her transcribe a letter to her son. The boy was used to transcribing letters into Arabic script – it was a service his father performed for the community. When his father was busy or tired, the father often delegated work to Abdoulaye and his brother Ibrahima. The brothers were happy to help. It was difficult work, but they loved to write.

“No,” the woman said, looking back up at him with sadness. “There is something I want to tell my son, but I don’t want anybody to know about it.” Again, her face fell. “But I can’t write.”

The woman’s struggle was not uncommon. To send a message, Fulani people had to translate messages into and back out of a script that was not their own, which was not fitted to their native tongue’s unique contours. Despite their best efforts, messages could be easily distorted.

Abdoulaye felt the woman’s heartache. He and his brother both longed for a writing system that their people could call their own.

One day, he asked his father:

“Why do we not have our own alphabet?”

The man shrugged. “All we’ve ever had is Arabic.”

From manuscripts to millions of monitors

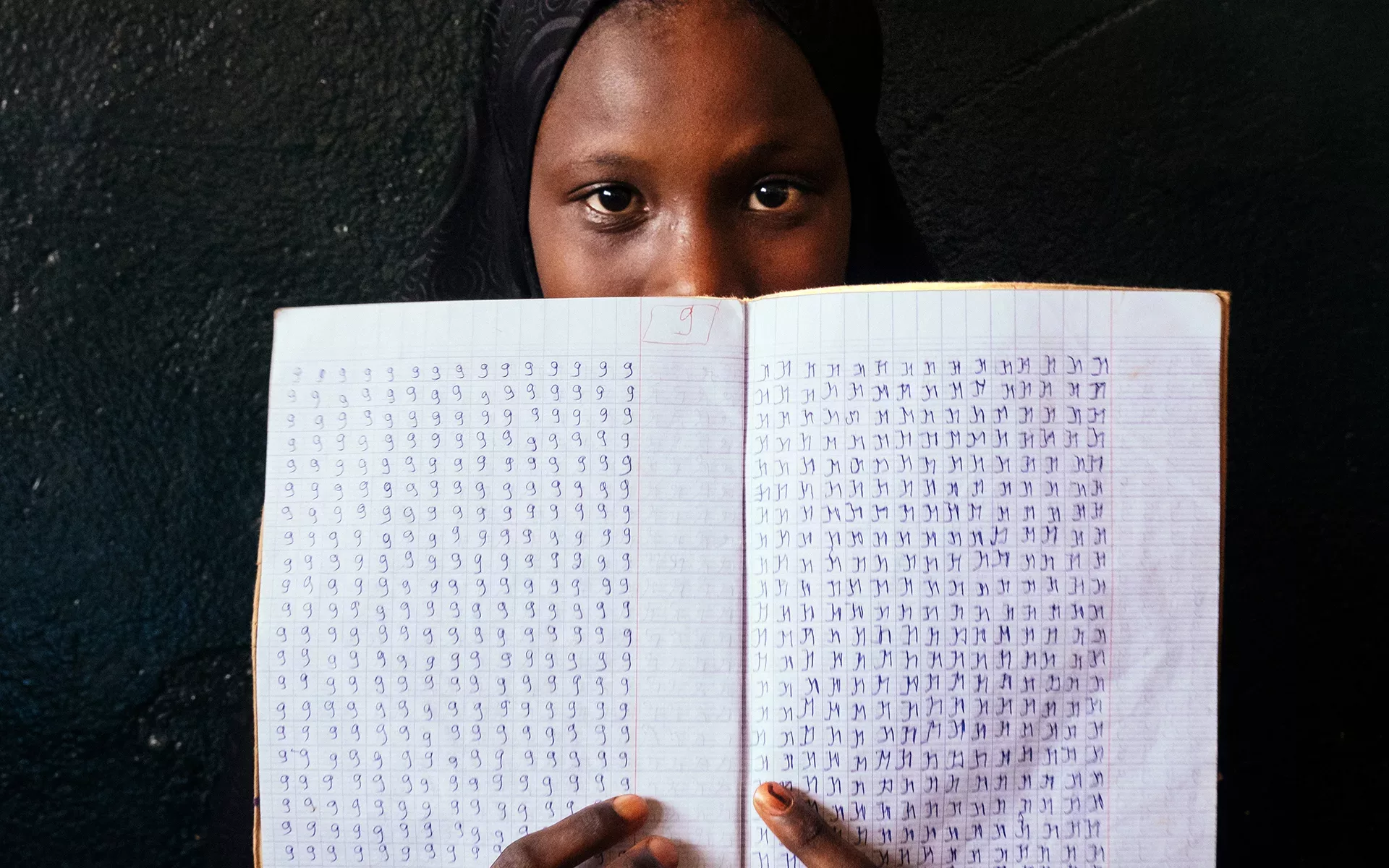

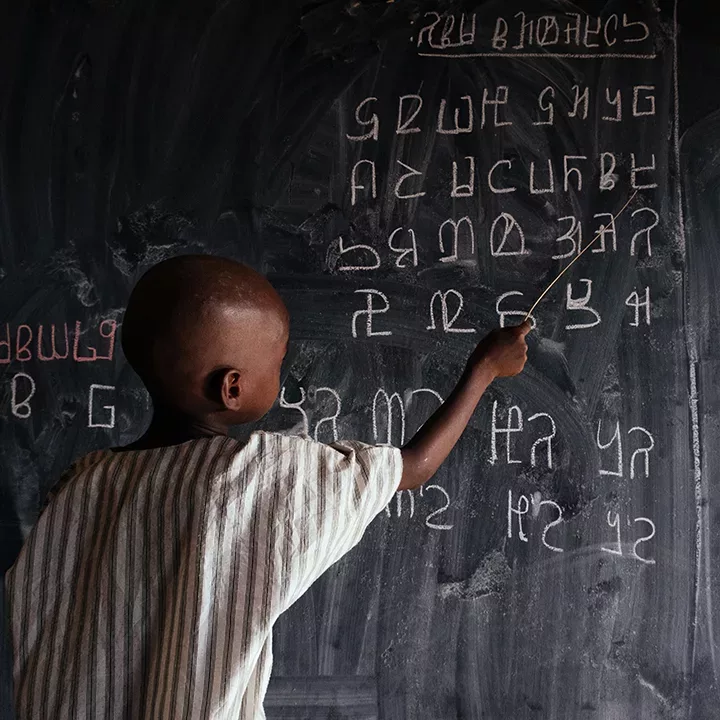

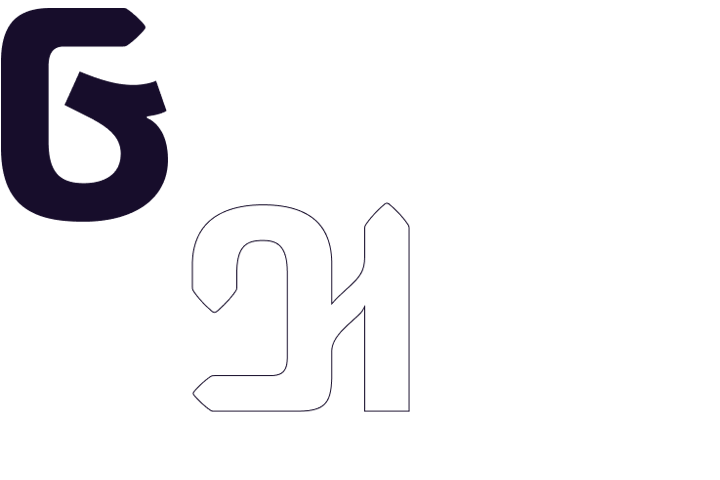

Ibrahima and Abdoulaye Barry began working on their alphabet in 1990, when Ibrahima was 14 and Abdoulaye was only 10. While their peers were outside playing, they huddled in their room after school, filling in composition notebooks with new shapes and assigning them sounds. Sometimes they closed their eyes, letting their hand guide the pen. Within six months they’d developed a working script: 28 letters, written right to left, like Arabic. The boys shared their alphabet with anyone who showed interest. First their sister, then their friends. They transcribed books, developed pamphlets and organized classes.

I used to spend sixteen hours a day writing, because I used to do everything by hand.

Over the following decades, the alphabet spread. But the brothers knew that their language needed to be accessible on computers and phones to reach a critical mass.

When the brothers moved to Portland, Oregon to pursue their studies, Ibrahima enrolled in a calligraphy class to improve his lettercraft. His teacher, impressed with the brothers’ mission, sent him to a calligraphy conference. Through this experience he met an editor with the Unicode Consortium, the independent non-profit that sets the standard for how scripts are depicted on screens. This encounter led to ADLaM’s inclusion in the Unicode 9.0 release in 2016, and later, its implementation in the May 2019 Windows update.

After nearly three decades, their life’s work could finally reach the global Fulani community.

But the Barrys are the first to acknowledge that the journey is far from over, and that the story of ADLaM is much bigger than them.

ADLaM has increased the chance of the language to survive, even in areas where the language has been dominated. We have our own alphabet! That’s a source of pride.

“It’s way beyond what we’ve ever imagined,” says Abdoulaye. “When we were growing up, I didn’t know that the Fulani language extended beyond even Guinea! It’s through this process that I discovered that the Fulani are all over West Africa.”

“It has also connected the Fulani from different countries,” says Ibrahima. “We had a convention in 2018 in Guinea, and we had people from 34 countries. The writing has connected people.”

The next generation of ADLaM

Despite the tailwind of institutional support that now propels ADLaM’s expansion, there is perhaps no more powerful signal of its success than watching the smile of satisfaction on a child’s face as she successfully recites ADLaM text.

Zainab Cherif Sow, a Fulani woman living in Rockville, Maryland, was frustrated with using other alphabets which couldn’t fully articulate what she wanted to say. Several years ago, she searched online and found some ADLaM instructional videos.

Today, the family texts with their relatives in Africa in ADLaM. Zainab runs a WhatsApp group for ADLaM learners. Two to three people request to be added to the group every day.

ADLaM has fostered a grassroots learning movement fueled largely through social media. Abdoulaye says that he and Ibrahima used to hear mostly about adults learning ADLaM, but increasingly it’s now children. Zainab teaches her children ADLaM twice a week. Fatima, the eldest, teaches her younger siblings. For Zainab, ADLaM represents more than just another way for her children to read and write. She wants her children to learn, remember and cherish their native tongue. But growing up in America, Fatima and her siblings face tremendous ambient pressure to speak, write and even think in English.

With these lessons, Zainab gives her children letters that they can see, that they can conjure on the blank page. In visualizing these words, the children are more likely to remember how to speak them. These words and sounds are theirs, a link to their past, and a reminder of who they are.

In 2023, the educational opportunities to learn the ADLaM alphabet have continued to expand. A new typeface, ADLaM Display, has been made available as a free download to use on Microsoft 365 apps and elsewhere—connecting Fulani people across the globe. The alphabet has also been recognized as an official alphabet by the government of Mali—clearing the way for children to learn ADLaM in government run schools. And in Guinea, schools that are fully dedicated to teaching with ADLaM as the primary alphabet are currently under construction.

These momentous steps will not only help ensure the next generation of Fulani people will be able to express themselves in their native tongue, but also create a richer, even more unified culture for generations to come.

Despite the Barry Brothers’ life-long commitment to spreading literacy through ADLaM—only text fonts for the alphabet existed, making it difficult for people to use the alphabet to communicate on social media platforms, which is now the most important means of communication for the Fulani people.

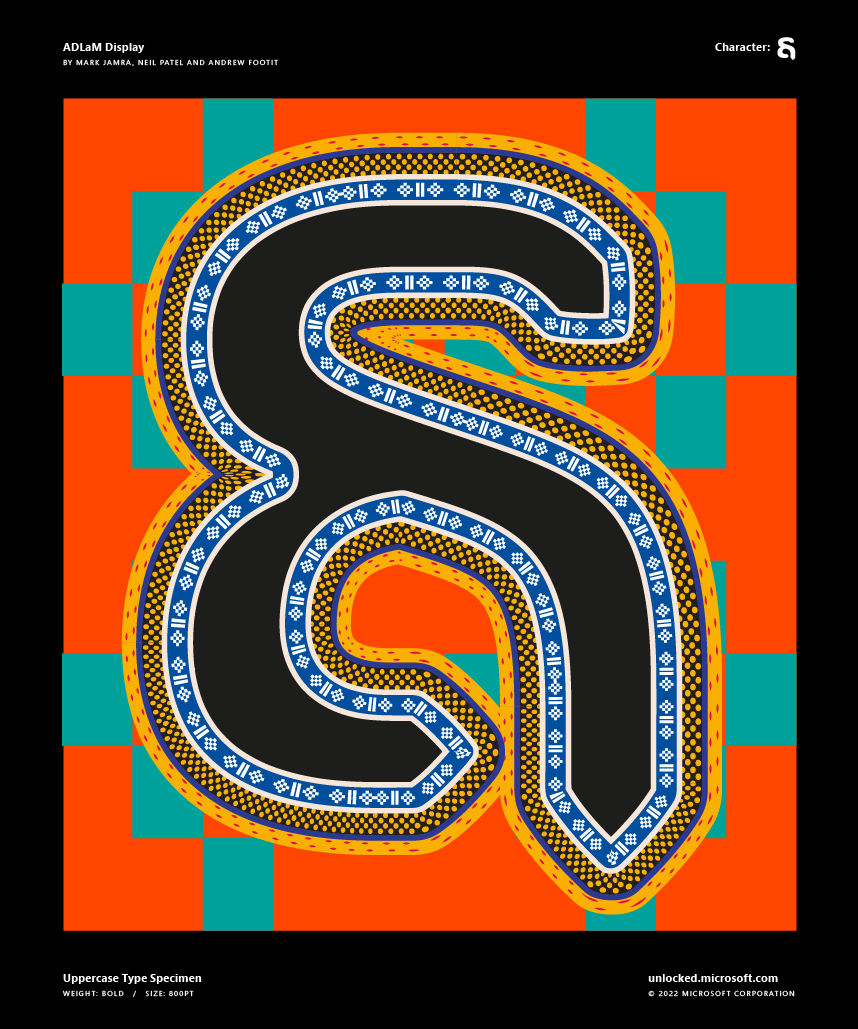

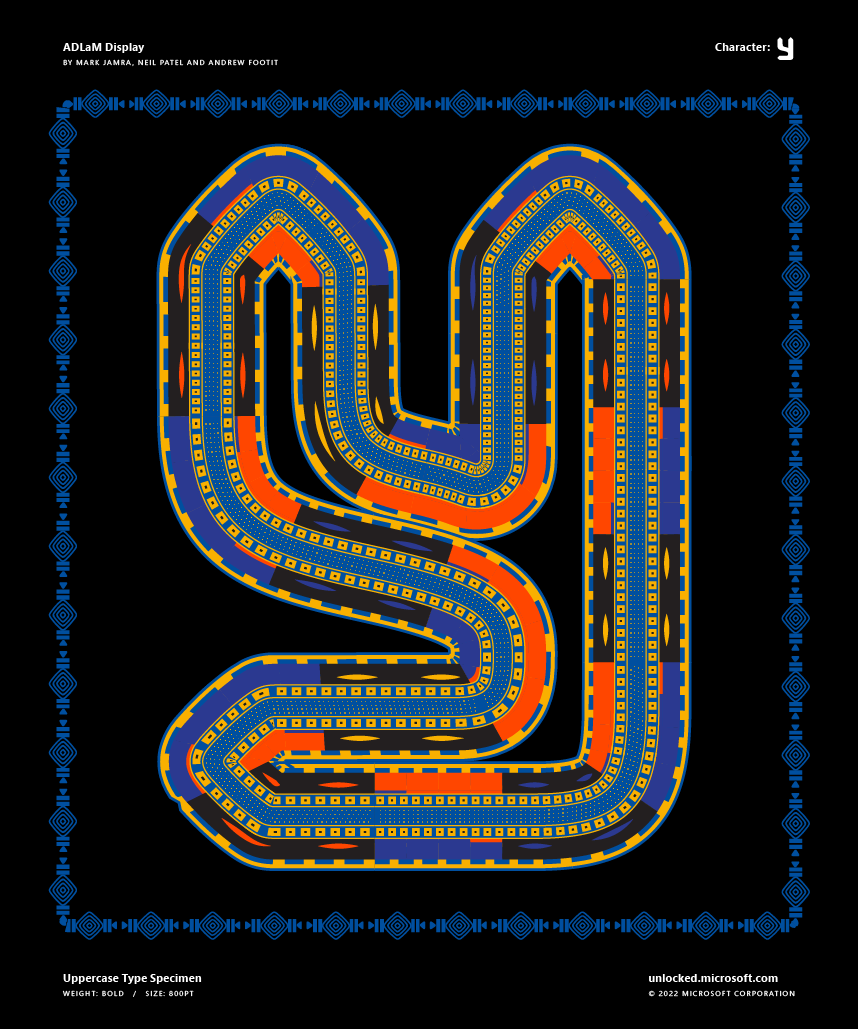

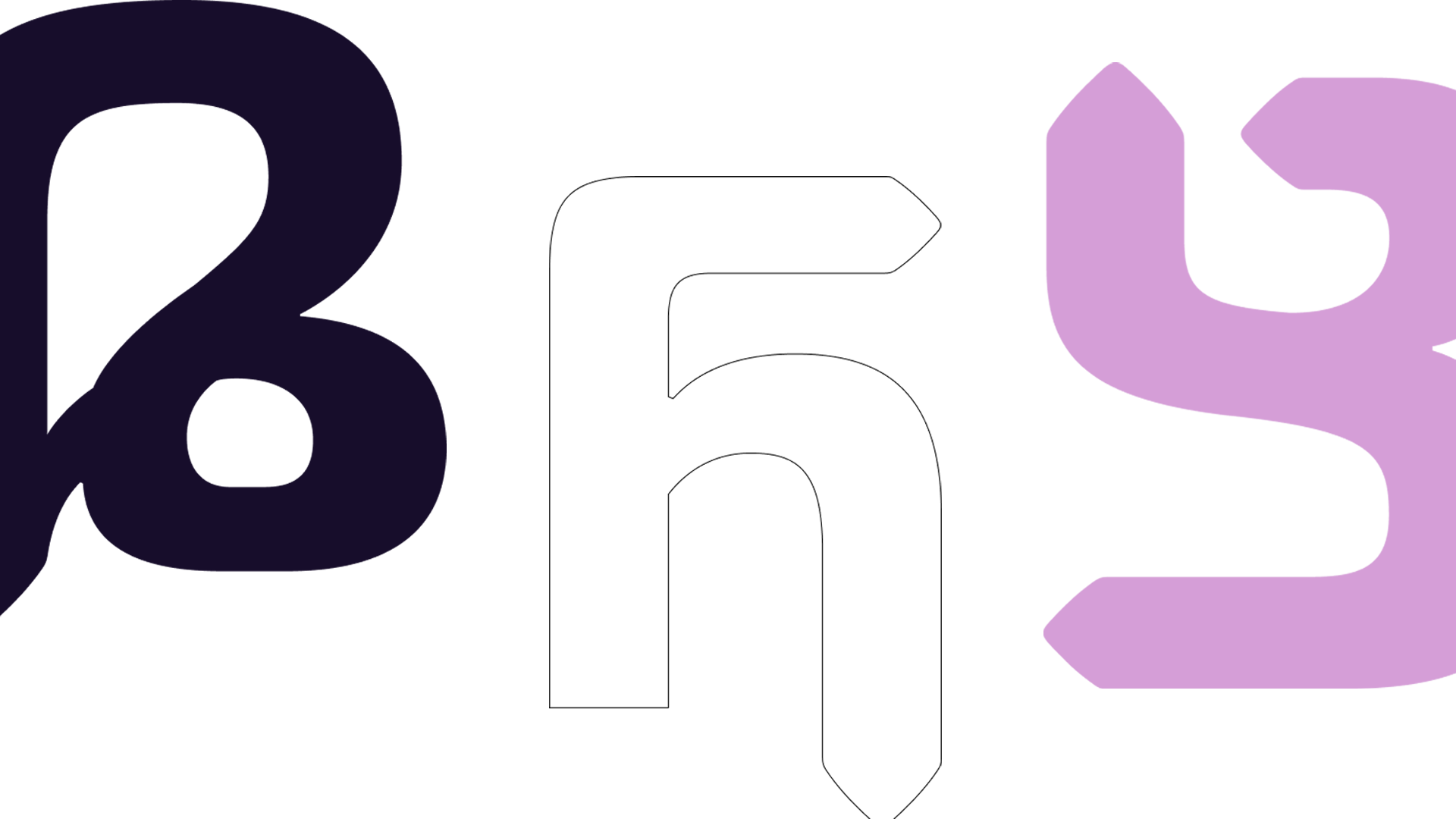

To help remedy this, we commissioned three renowned type designers Neil Patel, Mark Jamra, and Andrew Footit to create a new display font which specifically caters to these platforms.

The team created the ADLaM Display by taking inspiration from the spots, triangles, lozenges and chevrons patterns found in traditional khasas (blankets), Wodaabe (hats), and textiles of the Fulani culture.

ADLaM Display includes ADLaM’s most up-to-date characters. We also created a series of typographic artworks which are a further expression of Fulani visual culture. All are free to download and share.

If you are Fulani, part of the diaspora or just interested in learning more, here are a few ADLaM educational resources used in schools for those just starting out.