Mischievous. Restless. Curious. That’s how Ruma Akter describes herself as a child growing up in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Cutting class to go to the zoo. Always seeking to satisfy her busy and inquisitive mind. And curious about everything, particularly the gorgeous textiles and garments she’d see the women in her community sewing in their spare time. “My mother always encouraged me to learn new things, and I was so curious about tailoring and sewing. If I saw the neighborhood aunties stitching something new, I’d sit with them and not budge until they told me what they were doing. I really annoyed them!” Ruma recalls.

Ruma begged her older sister, who had taken stitching classes, to teach her more about the craft. She relented, and Ruma’s tailoring journey took off. Eventually, she made her first piece of clothing: a three-piece dress in sky blue. Ruma’s father even bought her a sewing machine so she could learn more advanced techniques.

As Ruma grew older, she followed the path of many other women in her life. She left school, got married, and had a child. Tailoring took a backseat.

Until she needed it more than ever.

Ruma (center) with her trainees in their community

Ruma and her daughter at home in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Sewing for a living

After several years of marriage, Ruma separated from her husband. A newly single mother, she faced a dilemma: how would she take care of her young daughter?

She found work as a garment machine operator, becoming the first in her family to work in a factory. She stitched pockets into shirts with a sewing machine. She was earning enough to support her family—and she was sewing again. “Many women in my neighborhood also worked in the factory, and we enjoyed being together. It was busy work, but I liked it. And once I got focused, the rest of the world would just fade away.”

One day, Ruma caught wind of a rumor.

Pssst, did you hear?

Hear what?

A new machine arrived at the factory today.

Yes, and?

It can sew…using a computer.

“Whenever factories get new machines that use technology, men are chosen as operators. Women are not given a chance. I was afraid. I didn’t know if I would have a job anymore—then how would I continue to provide?”

Where do our clothes come from?

Quite possibly, they come from Bangladesh.

It’s one of the leading textile exporters in the world and a major player in the global textile industry that employs an estimated 75 million workers.

Of this workforce, about 80 percent are women. But, despite being the overwhelming majority, female garment workers are often relegated to entry-level positions. Thread cutters. Button stitchers. Sewing machine operators. Pocket joiners. Women imbue our clothes with a crucial human touch. Yet, they’re most at risk of being displaced by automation.

Over the next several years, it’s estimated that over 50 million people will lose their jobs to technology. Most of them women. Like Ruma.

The rise and fall of a factory town

Sarah Krasley has been working in Bangladesh for the last ten years, but grew up a world away—in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where the legacy of factory work runs as deep as the Lehigh River snaking its landscape. “Allentown was a factory town. We had steel factories, garments factories, Mack Trucks, and Western Electric. I remember playing in the shadows of the abandoned silk mills as a kid and thinking it was a city from a fairy tale that had been frozen in time,” she says.

Sarah’s grandfather spent 42 years running the blast furnace at the Bethlehem Steel Factory, where her dad and uncle also worked summers in their youth. But as globalization and automation lured jobs away, Allentown struggled to modernize.

Bethlehem Steel shuttered. The silk mill jobs left town. One by one, factories fell like dominoes.

Their collapse left thousands without work and plunged Allentown into a decades-long recession.

It’s devastating when factory jobs dry up. Of this, Sarah is painfully aware. But she’s also aware of the damaging effects of factory work itself. “My dad worked in the ingot department and the story goes that after his shift, he’d change out of his coveralls, shower, and change into a clean, white shirt before leaving the factory. But because his pores were so grimy from the filthy air, by the time he got home his sweat had stained his shirt charcoal grey. That really hit home how this work is unsafe and should be performed by machines—but that people and machines can work together. The dirty, dangerous, and boring work can be done by machines and workers can be upskilled to do higher value, safer work.”

Why can’t it be efficient and fair? That’s the work I’m interested in doing forever.

Everyone deserves a fair shot

As she studied industrial design, went to business school, and developed technologies that helped manufacturers digitally transform, the shadow of Allentown’s abandoned factories loomed large in Sarah’s mind. “I’ve always known that automation has an unfair advantage”. It’s safer, it costs less, and it will never strike or call in sick. So, I felt like I needed to step in and say, ‘hey, let’s make sure that as technology gets better, people aren’t left behind—it can be a ‘both and,’ not an ‘either or.’ Because everyone deserves a fair shot.”

In 2016, she created Shimmy Technologies to fight for this fairness. Shimmy is a innovative, ed-tech company that provides technical skill development (called “upskilling”) to garment workers so they can learn to operate multiple machines and gain the digital literacies they need to work on new, automated machines. Workers take bite-sized, digital tutorials on Shimmy’s app, learning things like machine operation, terminology, techniques, and machine care.

To pilot Shimmy, Sarah turned to female garment workers in Bangladesh at the greatest risk of being erased from the workforce.

Sarah Krasley and Ruma Akter in Dhaka, Bangladesh

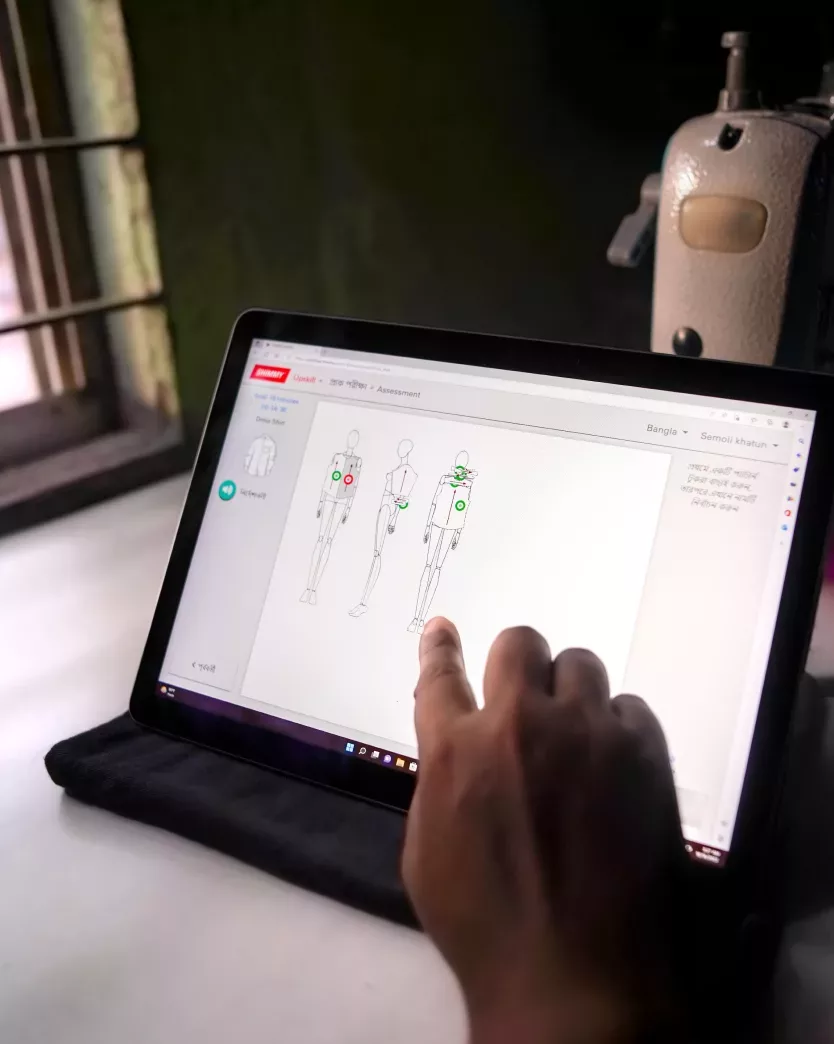

Shimmy’s digital tutorial

Shimmy students in a group training session

Re-skilling the skilled

Think about an ornately stitched wedding dress. Or a paisley shirt exploding with color. A person crafted those garments, using years of expertise. Sarah explains: “The people who make our clothes are highly skilled. So, why don’t we upskill and re-skill the folks with that innate ability?”

Many of the women receiving Shimmy’s training have not had the opportunity to pursue formalized education. Shimmy’s technical skills training program is often the first time they’ve used a computer. With the guidance of Shimmy’s team of Trainers and User Advocates, workers learn how to navigate the app on a Microsoft Surface Go tablet. The training uses digital games and quizzes, and follows up with TikTok videos to encourage learning and retention.

I felt like I could learn the same skills and achieve the same promotions that any man could.

For Sarah, Microsoft made perfect sense as a technological partner. The organizations have similar missions to use innovative technology to empower a better, more equitable future for everyone. And they also share central values around fundamental rights and inclusive economic growth. They know that for the world to succeed, the most disadvantaged need to succeed. And that this success depends on increasing access to digital skills and job opportunities.

By 2025, Microsoft has pledged to help train and certify 10 million people from underserved communities with in-demand digital skills. As Sarah sees their partnership, “The core philosophy that drives our work is that we as technologists have a say in the future of work. Automation is not a foregone conclusion for job loss simply because the technology exists. It doesn’t have to be a death sentence, as long as conscientious people are looking out for ways to optimize labor alongside that shift in a solid business case. Why can’t it be efficient and fair? That’s the work I’m interested in doing forever.”

Shimmy offers personalized trainings in multiple languages. With Microsoft Azure’s global reach, they can scale their programs to any potential trainers and trainees around the world. So far, Shimmy has piloted the software in the U.S., Bangladesh, and Indonesia, and is currently scaling up to reach 9,000 workers in 2023.

Ruma and her fellow trainers have trained over

2,125 women

In 2023, Shimmy’s goal is to train

9,000 workers

A female-powered future

Despite her initial apprehension about automation, Ruma enrolled in a Shimmy upskilling course and learned to operate a tablet. “At first, I was nervous—I had never touched a tablet before. But, after using the app, my anxiety quickly disappeared. I wanted to learn more!” Her curiosity blossomed into confidence. Confidence bloomed into opportunity as Ruma pursued new paths that she couldn’t before.

One of those paths? Becoming a Shimmy trainer herself. “When automated machines entered my factory, I didn’t want to be left behind. And I realized that this was a great opportunity to help others who feel the same. We can be the future of the garment industry.”

Ruma and her fellow trainers have trained over 2,125 women to date. Like her, many of Ruma’s trainees enter their first day feeling a whirlwind of emotions. How can you make clothes using an app? Will I be able to use the tablet? Can women even become supervisors? With her encouragement, these fears evaporate. “They realize they aren’t stuck in one place. And that, if a man can become a lead supervisor, so can they! They have renewed ambition to step into better roles.”

Many of Ruma’s students go on to receive higher pay and promotions, which fills her with joy. Having a higher salary doesn’t just mean they can live better today, but also tomorrow. “My daughter is seven years old. My opportunity with Shimmy allows me to provide for her present and future education. And I can look after my parents and younger brother. This has been wonderful for my whole family,” says Ruma.

Ruma continues training more women and mastering additional software.

She believes Bangladesh is entering an era of empowerment. One where factory workers can embrace the digital skills of the future. And where women can be leaders and create prosperous lives for themselves. Generation after generation.

“We will keep progressing together, always moving forward. There is no end to learning.”

Shimmy Technologies helps the world’s leading companies optimize work between humans and machines with innovative, thoughtfully designed technology. Founded by Sarah Krasley in 2016, the female-led, ed tech company has trained over 2,125 people. Clients include H&M, VF Foundation, and Zalando. Shimmy is a graduate of MIT Solve, Acumen Fund’s CivicX Future of Work Accelerator, and the New York Fashion Tech Lab.